viewpoint

May 2015

with John Barnes – Managing Director

Farming in the next twelve months will be a challenge for many, particularly for dairy farmers. It is times like this that concentrate the mind on things that must be achieved rather than those that we would like to happen at some point. There is a quote from Sir Ernest Rutherford from many years ago and it is on precisely this point…

“Gentlemen, we have run out of money. It’s time to start thinking”

Budgets are going to be stretched and of all the myriad issues that need consideration, the ones that are most important are those which maintain the farm and maintain production. Expensive add-ons that we all allow to slip into our business systems when times are good are the first to go and there is some other easy stuff which most farmers would have dealt to when the first signs of dark clouds appeared. But it is the harder items that really cut into the core operations of our business which are the ones that keep us awake at night and exercise our minds as per the quote above.

I have to do this in my business too and so I know what it takes. Sometimes when considering these nasty cuts it pays to also consider changes to our business systems. When the brain starts to travel down different lines of thought we can even get excited again by looking at options not considered seriously before. Some of those options can require quite profound change that will lead to increased profitability, and that is what it is all about when times are tough.

All of our clients when looking at nutrient budgets are also looking at financial budgets and considering both, which is just common sense. I have never held the view that you can just chuck a bit more fertiliser on because it is money in the bank. That is simply glib nonsense and I have no patience with those attitudes. Every dollar spent on fertiliser must have a financial return of more than the dollar spent, otherwise you should leave the money in the bank.

I have repeated time without number that we are wasting a lot of money on fertiliser. I think I wrote about it a while ago but it is worth repeating. I had a long conversation with a middle aged well qualified adviser of some note who was advising his clients on steep sheep country to cut back on fertiliser. He said the grass species on these properties were sub optimal and could not use all of the nutrients being thrown at them and the result was wasted money. What a breath of fresh air that conversation was, and a win for common sense, I must say. I thought my concerns over recent years about applying more nitrogen and more super on to the land no matter what the circumstances were falling on deaf ears… but maybe not.

Without getting into very sensitive territory the leaching of nutrients into waterways is not only a problem for our environment, it is also a huge waste of money. Who would keep putting petrol into a leaking fuel tank year on year without doing something about it? Very few people I would suggest.

In a search for efficiencies in tough times all of us must look at the big ticket items. On farms, most of my clients tell me that the biggest item of expenditure is interest and mortgage repayments followed by fertiliser. It makes good business sense to look at the second item which is fertiliser, because mortgages are pretty much out of your control unless you don’t have one. The first thing to consider when looking at fertiliser expenditure is… “Will any change I make result in a loss of production?” The “throw more on, its money in the bank” brigade will holler “YES”. I say “NO” providing you do it correctly. We regularly save money on fertiliser for our clients who come off what is now regarded as a standard programme. These high cost, high waste programmes were not standard even ten years ago, I might add.

Our fertiliser programmes look at a phosphate and nitrogen release of nutrients to the pasture plants over a period of time, and unless you are going to apply fertiliser monthly which is high cost, that is an optimum outcome. We have field trials that show even in a situation of feeding brassicas in wet puggy conditions there was virtually no nutrient leaching or runoff. This means all the money you expend ends up as meat wool or milk, with no waste of product or dollars. There are ways of doing more with less expenditure and that trick is called efficiency. In tough times this is what we must strive for.

A recent article from a regional local body sustainable agricultural adviser stated that a milking cow will excrete 70% of the nitrogen they consume. This means that those urine patches everybody worries about come directly from the bagged nitrogen applied to the pasture. So we have to be careful about what we apply, and that is my point.

We can do it better and we can make substantial savings but we have to do it slightly differently. If you always do what you always have done, you will get what you always got, and in the case of nutrients we know that what we always got is beginning to cause problems both environmental and financial.

Look at some new more efficient ways of doing things by phoning one of our company representatives who will provide you with options that will help you through the dilemmas farmers are now facing. We are qualified and keen to help.

John Barnes

Managing Director

Cadmium

There is a problem looming within the farming sector in New Zealand as it is everywhere in the world.

What is the problem with cadmium?

Cadmium is found in many forms and in small amounts is not harmful to animals or humans.

It is found in many types of rock formations including phosphate. Because of this it will be found in all phosphate fertilisers. The only factor then is how much will be found in in any given product. The various deposits of phosphate around the world have different amounts of cadmium within them. So how does this impact on the products we currently use within New Zealand?

Because we are a long way from most of the major mines in the world we used what was the most convenient and closest to our farms. Unfortunately this also had high levels of cadmium. This has led to some of our farms having detectable levels of cadmium in the soil. Our farming leaders have told us that all is well but I haven’t seen their scientific research papers to verify their claims. The upper level of cadmium allowed to be applied to our soils is 280 ppm, which I still consider to be too high. The lowest level of cadmium for the major companies will be down to 160 ppm. The Fertilizer New Zealand ideal standard is 20 ppm. Some of our fertilisers are down to as low as 6 ppm.

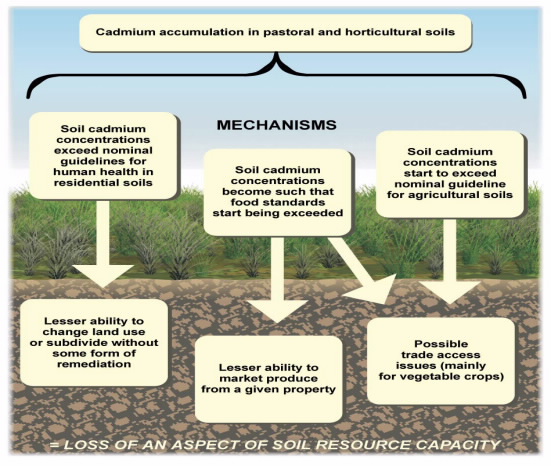

So why is cadmium an issue? Cadmium is an element which is only required by animals in very small amounts. What is not required is filtered by the body and stored in the kidneys. In mammals it accumulates in the major organs (kidneys and liver). As a result, the sale of these organs from cattle and sheep over 18 months old are banned for human consumption in New Zealand. There are many side effects to cadmium toxicity for humans. Scientist Mike Joy describes;

The problem for humans is that vegetables take up cadmium from the soil so this carcinogen is ingested by us when we consume those plants and then slowly builds up in us. It’s very hard to decide on a safe level of cadmium in soils to keep our intake below danger levels. Currently food standards are used as a guide, the theory is that if soil cadmium is kept below a certain level it should mean that in vulnerable crops like potatoes, onions, root and leafy vegetables and most grains, the standards will be met and we will be safe. We know very little about the health effects of long-term cadmium accumulation so the supposedly safe levels of consumption are changing globally.

However, if we use the European standard then the latest results of our 5 yearly total diet survey horrifyingly shows that New Zealand toddlers, infants and children already eat cadmium at, or near, the limit and the rest of us are not far behind. The World Health Organisation standard is more lenient and New Zealand uses this limit so the figures look a bit better.

Of course using these more lenient guidelines might backfire if New Zealand standards are not accepted by Europe; it could have potentially huge ramifications for our markets there.

There is no good news for the future either, the national cadmium report produced by Government revealed that on-going cadmium accumulation in our agricultural soils has the potential to increase dietary intakes in the New Zealand population.

So what has the fertiliser industry and government done about this issue?

Apart from producing a national strategy and setting up a working group dominated by industry representatives virtually nothing has changed in the four decades since cadmium accumulation was first identified as a problem.

Not surprisingly given the industry domination of the working group there is no evidence of net reduction in the rate of contamination.Every year, about 2 million tonnes of superphosphate fertiliser is applied to pastoral and horticultural soil in New Zealand, so that means we are adding a whopping 30-40 tonnes of cadmium per year.

It is time that we stop and think not just about our future but the future of our country. We must surely change to fertilisers with less cadmium content and, I might add, the sooner the better. In the meantime there needs to be a monitoring system set in place such as compulsory testing for cadmium with every soil test taken. If there isn’t a problem then no one need worry about one additional test to a farmer’s overall soil testing programme and it will assure our valued overseas clients that all is well down on the farm.

Whatever happens, change must take place.