viewpoint

February 2015

with John Barnes – Managing Director

FARMING PROFITABLY IN DRY CONDITIONS

Unfortunately, in the last few years we have seen a return of dry weather setting in across vast areas of our agricultural land. I have first-hand experience of some serious dry spells, and without being pessimistic, they have followed a similar pattern to that which we are experiencing now, and this could persist for a few more years. In the 1960’s, I remember killing sheep on the farm and seeing rocks in their stomachs, such was the shortage of feed.

I am told that the Government and farmer groups are progressing towards fairly large irrigation schemes as quickly as they can, but even some schemes that are in place now are running low on water. I understand that we only harvest around 2% of our total rainfall, so we have plenty of scope to enlarge our irrigated lands. Cost is an ever present issue, and not all farms can carry the burden of more overheads. We must trust that our farming leaders are pushing as hard as they can for access to more water at an affordable cost. Where water is available, I have seen vast improvements in the carrying capacity of the land and lowered stress levels of our farming families.

While we wait for the irrigation schemes, we need to change some of our farming practices to take account of the drier seasons. In my travels visiting farms across both islands, I have witnessed some very good results from those farmers who have bowed to the inevitable and planted some alternatives to the normal grass species. There are plants which are more drought tolerant and have been proven over many years, and they may have to be considered again. These include lucerne, chicory, plantain, various clovers and other grasses such as prairie grass. In wetter seasons we have tended to go back to our english grasses which are great. But when it turns dry, as it has done recently, I am suggesting we accept that turn of events, and head back to some old standbys for at least a few years.

My business is fertiliser and so naturally we sell and promote our products, but not at the expense of common sense. Recently I was talking with an eminently qualified advisor who has a lot to do with large farms in the North Island. He told me that he was advising his clients on some of the East Coast stations to cut back on the amount of fertiliser they were applying. Why? Because to quote him, “There is only so much growth that you are going to get out of a brown top dominant pasture, no matter what you throw on it.”, “Much of it is good money wasted”, he reckoned.

I nearly had a heart attack on the spot!!! This is what I have been saying for years, and sometimes I despair at how many times I have to repeat the message. Back in the old days the application of fertiliser produced astounding results because the rough pastures of the day had never seen the stuff before. Then, by some totally unscientific method more akin to the thinking of money lenders, our advisors just kept on advising more and more fertiliser, as though grass was going to grow in ever increasing amounts in tune with the amount applied. Just like compound interest!!!!

Soil biology simply does not work like that! I get very frustrated with some folk in our advising community who should know better than to promote this waste. In my view, too much fertiliser can cause just as many problems as too little. A quote that sticks in my mind is, “The right fertiliser at the right time in the right amount”, and this is what we practice at Fertilizer New Zealand. The idea that you can pile ridiculous amounts on and consider that to be “money in the bank” makes no sense to me at all. In fact, if it weren’t so costly to do so, one would apply a small amount of fertiliser each month and that would actually make more sense than applying huge amounts and expecting it to be drawn down over time like money in the bank.

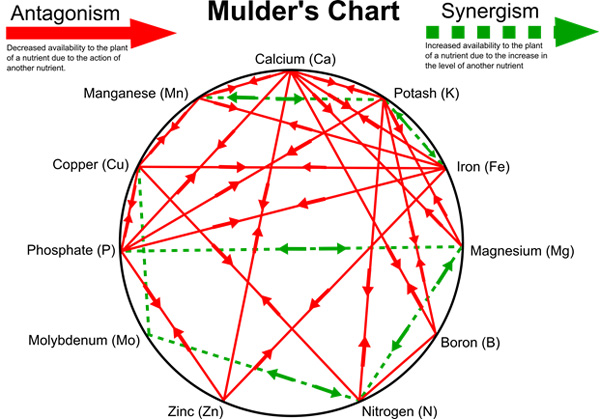

In nature one element will have a reaction on another, sometimes beneficial and sometimes detrimental. Mulders Chart (below) goes some way to explaining these interactions.

It worries me a lot how we have become so complacent in New Zealand agriculture with our dependence on just a few major products poured onto our land almost ad infinitum, especially in light of our well recorded and concerning nutrient leaching problems. In the future, we must be far more discerning in taking account of our various soil types, our soil biology and (as I have mentioned above) the way we apply our fertiliser.

We must get over the attitude of “one size fits all”, chucking heaps on and excusing that away by saying that it is money in the bank. Money down the river is more the truth of it! There are some really smart people that I am working with on the machinery manufacturing side of our industry, and they are getting ever closer to my ideal of the right fertiliser at the right time in the right amount. We will get there, of that there is no doubt, and an increasing number of people are getting with the programme. They “get it” as my grandkids would say. We have tailored our liquid products to fit in with some of the increasingly sophisticated machinery that is around now for those who choose spray application. We believe that this method will become increasingly popular due to ease of operation and precision.

John Barnes

Managing Director

Antagonism

Mulders Chart shows some of the interactions between plant nutrients

High levels of a particular nutrient in the soil can interfere with the availability and uptake by the plant of other nutrients. Those nutrients which interfere with one another are said to be antagonistic.

For example, high nitrogen levels can reduce the availability of boron, potash and copper; high phosphate levels can influence the uptake of iron, calcium, potash, copper and zinc; high potash levels can reduce the availability of magnesium. Thus, unless care is taken to ensure an adequate balanced supply of the nutrients – by the use of analysis – the application of ever higher levels of nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium in compound fertilisers can induce plant deficiencies of other essential nutrients.

Synergism

Synergism can occur when the high level of a particular nutrient increases the demand by the plant for another nutrient.

Increased nitrogen levels create a demand for more magnesium. If more potassium is used, more manganese is required and so on.

Although the cause of synergism is different from that of antagonism, the result is the same; induced deficiencies of the crop.

High levels of molybdenum in the soil and in the herbage reduce an animal’s ability to absorb copper into the blood stream, and ruminant animals grazing these areas have to be fed or injected with copper to supplement their diet (see Mo/Cu dotted line).

Is it possible that we have been given incorrect information and applied some elements which could be leading to or contributing to our on farm problems?

Take nitrogen as an example. If there is an imbalance [too much] of nitrogen, there will be a decrease in availability to the plant of copper, boron and potash. The outcome would be to drench with copper and boron and to apply potash fertiliser, which would then decrease the plant available magnesium.

This is why I believe in the way liquid fertilisers work so well. A scientifically balanced product will allow the plant to take up nutrients in a sustainable way, and will not suppress growth by decreasing the availability of the elements, but will stimulate the plant to grow to its full potential.

I recall independent trial work that shows a correctly balanced colloidal fertiliser with a suitable N.P.K (similar to Actavize) that produced more dry matter than a standard phosphate product. We are not surprised with the results.

During recent dry spells we have found our farmers have got through with limited problems. We constantly deliver crops and pasture that will hold on longer in the dry and start quicker after the rains start again. The reason for this is a stronger plant with a better root system. What we mean by a stronger plant is a better cell structure. Chemical fertilisers usually increase the cell size of the plant giving the appearance of a bigger plant. We fully acknowledge the plant will be manufacturing its own new cells through natural growth. Actavize increases cell growth through its unique use of elements and growth promotants.